On Viriditas, Maybe Veritas, and Virtuality

by Barbara Casavecchia

Through artist Hito Steyerl’s multimedia installation Power Plants and Hildegard of Bingen’s botanical viriditas, Barbara Casavecchia evokes the limits of contemporary macro epistemological models in their abstract design of reality.

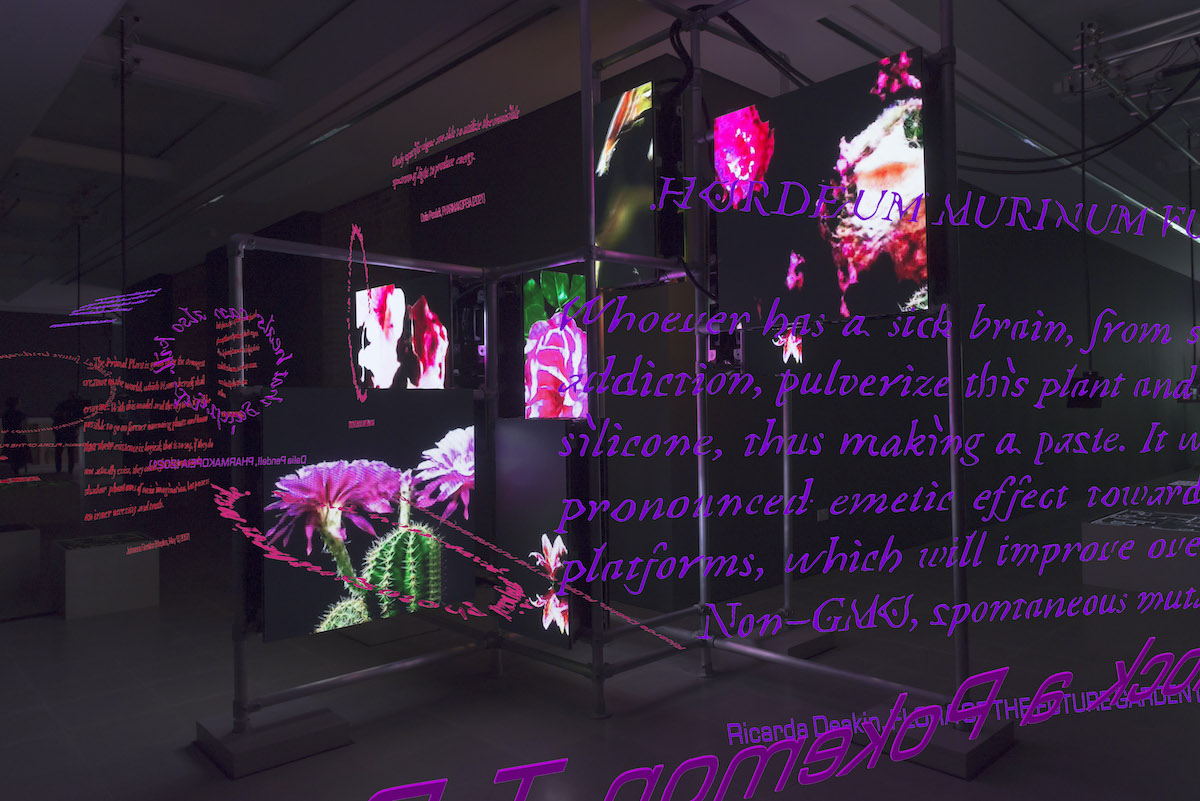

Hito Steyerl, Power Plants, Installation view, 11 April – 6 May 2019, Serpentine Galleries, London. AR application design by Ayham Ghraowi, Developed by Ivaylo Getov, Luxloop. Courtesy of the artist; Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York; and Esther Schipper Gallery, Berlin. Photo: © 2019 readsreads.info

Plants have many powers. Like that of anticipating the future by inscribing it in the present, projecting themselves forward one or many generations through their own seeds and replicating themselves through forms of vegetative propagation. A stem like the rhizome, for example, which grows horizontally underground and continuously spreads, makes it possible to propagate even in adverse environmental and climatic conditions. Knowing that there were cycles of germination in the past makes us believe that there will continue to be new seasons, one following another, even though the worsening of the climate emergency makes it more difficult to predict what they will be like and how long they will last.

Nevertheless, as observed by Anna L. Tsing in her book The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins, we cannot interpret or imagine the complexity of the phenomena underway on a planetary scale, claiming that the same conditions hold true at every point of the world; instead, we need to study the patches where a few of them are concentrated.1 Just as with the organic growth (that is, multispecies assemblages) of plants in a forest.2 The most common epistemological macro model for reading what we think is happening at ground level is still the artificial one of the plantation (a model in full crisis, because of its tragically colonial roots and because the tragic side effects of the cultivation of single crops are now abundantly clear), where the distribution of more-than-human individuals on the ground or in the water is abstracted, systematised and planned with the goal of simplifying calculations and methods for its infinite replication. It is a statistical model designed to evaluate industrial-pace horizons of growth and that, however, willingly forgets to associate them with the estimation of real environmental costs, like water and fuel consumption and levels of pollution caused by fertiliser.

Hito Steyerl, Power Plants, Installation view, 11 April – 6 May 2019, Serpentine Galleries, London. AR application design by Ayham Ghraowi, Developed by Ivaylo Getov, Luxloop. Courtesy of the artist; Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York; and Esther Schipper Gallery, Berlin. Photo: © 2019 readsreads.info

Broadly speaking, humanity presently has two models of knowledge at its disposal, and they operate at different speeds. The first, the knowledge-driven model, is a slow process based on factual knowledge, which is to say observations accumulated over time. The second, the data-driven model, is based on the interpretation of giant masses of harvested information, used to make fast, plausible predictions of the future. In this case, knowledge is codified as probability, recursive rule and set of relationships.

Prediction is the playing field for many of the key matches of the Capitalocene era, or Plantationocene era if you like. Like the apps that forecast rain, sun and the fluctuations of financial markets, with ever shrinking margins of time and reciprocal interconnections. The construction of models (also known as ‘modeling’) is increasingly hypothetical and heuristic in nature, and the more classic methods of machine learning have now been joined by deep learning, which references algorithms inspired by the structure and rhizomatic functioning of the brain, through artificial neural networks. With the goal of resolving multiple complexities and non-linear problems as quickly as possible, while striving for increasingly precise and well-defined results, quantum computing promises further advances in the process of calculation and accelerated discovery.

And yet, clouds, storms, sudden downpours, typhoons, heat waves above and below the surface of the sea, acidification and desiccation rates, currents and disturbances never stay still in their places. In this epoch of change, they are even less predictable and the lines that try to mark out wet and dry, surfaced and submerged, salty and sweet, drenched and dry, shift, reorient and contradict the fixity of old maps and descriptions. It is unsurprising that the Nobel Prize in Physics 2021 was awarded to Syukuro Manabe and Klaus Hasselmann for their fundamental contribution to the “physical modeling of Earth’s climate, quantifying variability and reliably predicting global warming.”

Hito Steyerl, Power Plants, Installation view, 11 April – 6 May 2019, Serpentine Galleries, London. AR application design by Ayham Ghraowi, Developed by Ivaylo Getov, Luxloop. Courtesy of the artist; Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York; and Esther Schipper Gallery, Berlin. Photo: © 2019 readsreads.info

Some real data are, however, clear-cut. According to an FAO report, two-thirds of the planet’s biodiversity has been lost over the last century, and that it just for cultivated plants. Many botanical species have gone extinct and others are migrating towards more welcoming climates, but they do not always move quickly enough. Humans have tried to do something about this and take far-sighted action, creating an impressive central botanical bank by storing duplicates of all the seeds preserved in the world’s genebanks in a gigantic underground vault on an island in the Svalbard archipelago, where the low temperatures should ensure their preservation even if electricity is cut (although the permafrost is melting at an unexpected speed even just of the North Pole). From the vault’s inauguration in 2008 until 2015, only deposits were made, but then 116,000 exemplars were taken by ICARDA (the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Area), so that it could rebuild its collection of cultivated and wild plants, which had been kept in Aleppo and was destroyed by the war in Syria. ICARDA then came back later to deposit thousands of new exemplars, after having reintroduced them in the region to restart the agricultural production chain. The time frame of this episode showed how quickly a vast shared collection of seeds could have been lost.

As explained in a recent article published in the academic journal Horticultural Research, study of the relationship between deep learning and horticulture is rapidly expanding.3 Over the last five years, and based on the results of the algorithmic capacity to process billions of images and aggregated data, the focus has been on identifying and classifying plant species and on parasite and disease management, as well as recording plant quality, monitoring growth and predicting yields. But it should be kept in mind that this is, overall, about an ideal future horticulture, conceived and calculated as a coming event, rather than understood and tested live, with all the attendant uncertainties, contingencies and cruelly anthropic setbacks.

Hito Steyerl, Power Plants, Installation view, 11 April – 6 May 2019, Serpentine Galleries, London. AR application design by Ayham Ghraowi, Developed by Ivaylo Getov, Luxloop. Courtesy of the artist; Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York; and Esther Schipper Gallery, Berlin. Photo: © 2019 readsreads.info

“I will never enter the future to look for my garden. Because it is already here:” these are the words of one of the voices in Hito Steyerl’s multimedia installation Power Plants (2019). It is the voice of Heja, a female prisoner who has hidden her garden to protect it from the violence of her jailers, who are merciless with every little plant that sprouts. She has hidden it in a future so close to the present that it anticipates it by just a few frames or fractions of a second: we are not inhabiting it yet but we can already see it. It is one of the paradoxes of our patchy perception of time (and of Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity) that it is, in effect, slowed down by speed. And devoid of a universal order in force everywhere in the same way. As Carlo Rovelli wrote in The Order of Time, “Our present does not extend throughout the universe. It is like a bubble around us. How far does this bubble extend? It depends on the precision with which we determine time. If by nanoseconds, the present is defined only over a few meters; if by milliseconds, it is defined over thousands of kilometers. As humans, we distinguish tenths of a second only with great difficulty; we can easily consider our entire planet to be like a single bubble where we can speak of the present as if it were an instant shared by us all. This is as far as we can go.”4 Past and future lie beyond that threshold, joined by an extended present that can only be site specific.

Hito Steyerl, Power Plants, Installation view, 11 April – 6 May 2019, Serpentine Galleries, London. AR application design by Ayham Ghraowi, Developed by Ivaylo Getov, Luxloop. Courtesy of the artist; Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York; and Esther Schipper Gallery, Berlin. Photo: © 2019 readsreads.info

Perhaps the garden of Power Plants is like that. A hortus conclusus or hortus sanitatis, like the medieval ones where nuns and monks cultivated aromatic and medicinal plants, the curative properties of which were meticulously described by the Benedictine abbess, writer, philosopher, mystic, composer, naturalist, healer and inventor of a personal lingua ignota with twenty-three letters, Hildegard of Bingen (1099-1179), in works like Physica (Natural History or Book of Simple Medicine) and Causae et curae (Book of Causes and Remedies or Book of Compound Medicine). In these texts, she recommended effective remedies for the melancholy, irascibility and intoxication that prevent the body from freeing itself from toxins, thus opening the door to disease. There are 230 plants and grains (most of which still around today) in Hildegard’s herbal, along with their relative properties and recipes for decoctions, compresses and washes that have travelled through the centuries with proven success. Recently, the philosopher Michael Marder wrote a meditation on Hildegard’s “ecological theology,” Green Mass, accompanying each chapter with a musical score by cellist Peter Schuback.

In the Prelude to the book, Marder reflects on the metamorphic and germinative power of Hildegard’s concept of viriditas (understood as “a self-refreshing vegetal power of creation ingrained in all finite things”5), seeking “whatever still remains of vitality in the creases of life’s material and spiritual dimensions, contemplative and engaged attitudes, visual and auditory registers.”6 The articulation of our “mental-psychic-spiritual” and “material-extended-embodied” codes in non-binary terms of vitality “has the potential to heal the split […] responsible for putting the planet on the brink of an environmental disaster.”7 According to Marder, a carpet of mystical flowers with multicolour petals springs from the exultation of viridity.

In Hito’s garden, immersed in darkness, perched on metal frameworks, powered by invisible and galvanizing flows of electric charge, future plants grow on vivid LED screens, positioned vertically like our omnipresent smartphones. Here too, as in the Hildegard-inspired echoes evoked by Marder, there is a soundtrack created by the artist in collaboration with the British musician and rapper Kojey Radical and the Japanese techno and ambient composer Susumu Yokota (together, the three released the album Power Plants 12”, 2019) to accompany its flowering and expand its reverberation. In this hortus digitalis, the classic superpowers (such as capturing carbon dioxide and transforming sunlight into energy, through photosynthesis) and vegetal agency abound, and salvific plants of the species Futuris, such as Hordeum Murinum, Sysimbrium Irio, Chenopodium Botrys and Urtica Dioica, prosper, clearing our minds of the confusion wrought by abuse of social media, purifying us of toxic sponsors, trolls and melancholy, blocking greenwashing, teaching us how to do nothing and be OK all the same, and pleasing the senses. In short, all species with the potential capacity to heal our alienation and re-enchant us, reintroducing us to the joys of the sensory world. Not immediately, but almost. Or perhaps never.

Hito Steyerl, Power Plants, Installation view, 11 April – 6 May 2019, Serpentine Galleries, London. AR application design by Ayham Ghraowi, Developed by Ivaylo Getov, Luxloop. Courtesy of the artist; Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York; and Esther Schipper Gallery, Berlin. Photo: © 2019 readsreads.info

The botanical images flash by, never perfectly in focus or resolved, in a state of constant metamorphosis. The transition from one to another is a continuum, because it corresponds to a flow of information that tries to configure itself as a recognisable pattern for a neural network. In her book Duty Free Art: Art in the Age of Planetary Civil War, Steyerl writes in this regard about automated apophenia.8 One might think that this mercurial striving to decipher and predict a certain botanical fact also signals the need to offset a cognitive dysfunction that afflicts all human beings: “plant blindness,” due to which, in spite of plant species being in crushing majority on our planet (about 85% of the biomass), our brains mostly register just the presence of animals, human and otherwise, relegating all the rest to a hazy background of insignificance.

PROJECTING HUMAN VISION IN THE ARC OF A VIRTUAL, AUGMENTED, IDEALIZED REALITY, ONE THAT IS SHAPED ACCORDING TO THE PREDICTIVE REQUIREMENTS THAT WILL NECESSARILY INFLUENCE OUR BEHAVIOR, ALSO MEANS MAKING THE ‘ACTUAL REALITY’ (IN THE ARTIST’S WORDS) INCREASINGLY LESS PERCEPTIBLE, UNDERGROUND, RUNNING BENEATH A PRE-PACKAGED SKIN THAT HAS NOT BEEN PROGRAMMED TO ALLOW MAGGOTS, MOULD, PATHOGENS, OR CRACKS.

What we are unable to see, in spite of it being always in front of our eyes and captured by cameras, is the real seed of the question, as well as a recurrent theme in Steyerl’s work.9 Considering it in light of the undisputed power of rejection of factual evidence and its implications — which has so forcefully emerged during the pandemic and crisis of global populism, toxically fertilised by systems of “artificial stupidity”, as the artist defines it — is inevitable. “Just because it seems convincing, doesn’t mean it is fact,” Steyerl observed at the end of a lecture on Bubble Vision.10 We know that images are now often what keep us in the dark, also monitoring us, controlling us, becoming our jailers, drying us up, robbing us of our vitality, movement and regenerative energy. Projecting human vision in the arc of a virtual, augmented, idealized reality, one that is shaped according to the predictive requirements that will necessarily influence our behavior, also means making the ‘actual reality’ (in the artist’s words) increasingly less perceptible, underground, running beneath a pre-packaged skin that has not been programmed to allow maggots, mould, pathogens, or cracks. If, as James Bridle writes in New Dark Age, the crisis of climate change is a crisis of the mind, thought and our capacity to imagine another way of being, then instead of relocating that imaginative power in an illusory future, we now need to plant it and root it in the extended present: the here and now.11

— Translated from Italian by Sarah Elizabeth Cree

Hito Steyerl is a filmmaker, visual artist, writer, and innovator of the essay documentary who lives and works in Berlin. She is Professor for Experimental Film and Video at the UdK – University of the Arts, Berlin, where she founded the Research Center for Proxy Politics together with Vera Tollmann and Boaz Levin. Her works have been shown in solo and group exhibitions in institutions such as the 58th Venice Biennale; K21, Düsseldorf; Serpentine Galleries, London; Kunstmuseum, Basel; Castello di Rivoli, Turin; Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid; Artists Space, New York; Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; the German Pavilion at the 56th Venice Biennale; and documenta 12, Kassel, among others. A selection of her essays are summarized in books such as Duty Free Art: Art in the Age of Planetary Civil Wars (London/New York: Verso, 2017); The Wretched of the Screen (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2012); and The Color of Truth (Vienna: Turia Kant, 2008).

Barbara Casavecchia is a writer, independent curator, and educator based in Venice and Milan, where she has been teaching in the Department of Visual Cultures and Curatorial Practices of the Brera Academy since 2011. She is Contributing editor of Frieze, and her articles and essays have been published in magazines such as art-agenda, ArtReview, D/La Repubblica, Flash Art, Mousse, Nero, South, and Spike, among others, as well as in artist books and catalogues. From 2021-2023, Barbara will lead the cycle The Current III promoted by TBA21–Academy at Ocean Space, Venice. With the working title “Mediterraneans: ‘Thus waves come in pairs’ (after Etel Adnan),” it acts as a transdisciplinary and transregional exercise in sensing and learning with, by supporting situated projects, collective pedagogies, and voices along the Mediterranean shores across art, culture, science, conservation, and activism. In 2018, she curated the solo exhibition “Susan Hiller, Social Facts” at OGR, Turin.

1 See Anna L. Tsing, Andrew S. Mathews, and Nils Bubandt, “Patchy Anthropocene: Landscape Structure, Multispecies History, and the Retooling of Anthropology,” Current Anthropology, vol. 60, S20 (2019), available online.

2 “…I find myself surrounded by patchiness, that is, a mosaic of open-ended assemblages of entangled ways of life, with each further opening into a mosaic of temporal rhythms and spatial arcs” in Anna L. Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2015, 4.

3 See Biyun Yang and Yong Xu, “Applications of deep-learning approaches in horticultural research: a review,” Horticulture Research, vol. 8, n. 123 (2021), available online.

4 Carlo Rovelli, The Order of Time, translated by Erica Segre and Simon Carnell, London: Penguin, 2018.

5 Michael Marder, Green Mass: The Ecological Theology of St. Hildegard of Bingen, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2021, 12-17.

6 Ibidem.

7 Ibidem.

8 See Hito Steyerl, Duty Free Art: Art in the Age of Planetary Civil War, London/New York: Verso, 2019.

9 Here, it is enough to cite the titles of the five “lessons” in her video HOW NOT TO BE SEEN. A Fucking Didactic Educational .Mov File, 2013: “How to Make Something Invisible for a Camera,” “How to be Invisible in Plain Sight,” “How to Become Invisible by Becoming a Picture,” “How to be Invisible by Disappearing,” and “How to Become Invisible by Merging into a World Made of Pictures”.

10 See Hito Steyerl, “Bubble Vision,” Serpentine Marathon: GUEST, GHOST, HOST: MACHINE!, YouTube, 07/10/2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=boMbdtu2rLE

11 See James Bridle, New Dark Age, London/New York: Verso, 2018.

Hito Steyerl is a filmmaker, visual artist, writer, and innovator of the essay documentary who lives and works in Berlin. She is Professor for Experimental Film and Video at the UdK – University of the Arts, Berlin, where she founded the Research Center for Proxy Politics together with Vera Tollmann and Boaz Levin. Her works have been shown in solo and group exhibitions in institutions such as the 58th Venice Biennale; K21, Düsseldorf; Serpentine Galleries, London; Kunstmuseum, Basel; Castello di Rivoli, Turin; Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid; Artists Space, New York; Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; the German Pavilion at the 56th Venice Biennale; and documenta 12, Kassel, among others. A selection of her essays are summarized in books such as Duty Free Art: Art in the Age of Planetary Civil Wars (London/New York: Verso, 2017); The Wretched of the Screen (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2012); and The Color of Truth (Vienna: Turia Kant, 2008).

Barbara Casavecchia is a writer, independent curator, and educator based in Venice and Milan, where she has been teaching in the Department of Visual Cultures and Curatorial Practices of the Brera Academy since 2011. She is Contributing editor of Frieze, and her articles and essays have been published in magazines such as art-agenda, ArtReview, D/La Repubblica, Flash Art, Mousse, Nero, South, and Spike, among others, as well as in artist books and catalogues. From 2021-2023, Barbara will lead the cycle The Current III promoted by TBA21–Academy at Ocean Space, Venice. With the working title “Mediterraneans: ‘Thus waves come in pairs’ (after Etel Adnan),” it acts as a transdisciplinary and transregional exercise in sensing and learning with, by supporting situated projects, collective pedagogies, and voices along the Mediterranean shores across art, culture, science, conservation, and activism. In 2018, she curated the solo exhibition “Susan Hiller, Social Facts” at OGR, Turin.

1 See Anna L. Tsing, Andrew S. Mathews, and Nils Bubandt, “Patchy Anthropocene: Landscape Structure, Multispecies History, and the Retooling of Anthropology,” Current Anthropology, vol. 60, S20 (2019), available online.

2 “…I find myself surrounded by patchiness, that is, a mosaic of open-ended assemblages of entangled ways of life, with each further opening into a mosaic of temporal rhythms and spatial arcs” in Anna L. Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2015, 4.

3 See Biyun Yang and Yong Xu, “Applications of deep-learning approaches in horticultural research: a review,” Horticulture Research, vol. 8, n. 123 (2021), available online.

4 Carlo Rovelli, The Order of Time, translated by Erica Segre and Simon Carnell, London: Penguin, 2018.

5 Michael Marder, Green Mass: The Ecological Theology of St. Hildegard of Bingen, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2021, 12-17.

6 Ibidem.

7 Ibidem.

8 See Hito Steyerl, Duty Free Art: Art in the Age of Planetary Civil War, London/New York: Verso, 2019.

9 Here, it is enough to cite the titles of the five “lessons” in her video HOW NOT TO BE SEEN. A Fucking Didactic Educational .Mov File, 2013: “How to Make Something Invisible for a Camera,” “How to be Invisible in Plain Sight,” “How to Become Invisible by Becoming a Picture,” “How to be Invisible by Disappearing,” and “How to Become Invisible by Merging into a World Made of Pictures”.

10 See Hito Steyerl, “Bubble Vision,” Serpentine Marathon: GUEST, GHOST, HOST: MACHINE!, YouTube, 07/10/2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=boMbdtu2rLE

11 See James Bridle, New Dark Age, London/New York: Verso, 2018.